11 Social and Behavioral Theories in Program Design and Impact Measurement

Successful interventions don't happen by chance—they're sculpted by understanding. Delve deep into 11 foundational social and behavioral theories driving effective program design. Learn their applications, their nuances, and why choosing the right theoretical lens can make or break your program's impact.

PROGRAM DESIGN & EVALUATIONSOCIO-BEHAVIORAL RESEARCH

The Power of Social and Behavioral Theories in Program Design and Impact Measurement

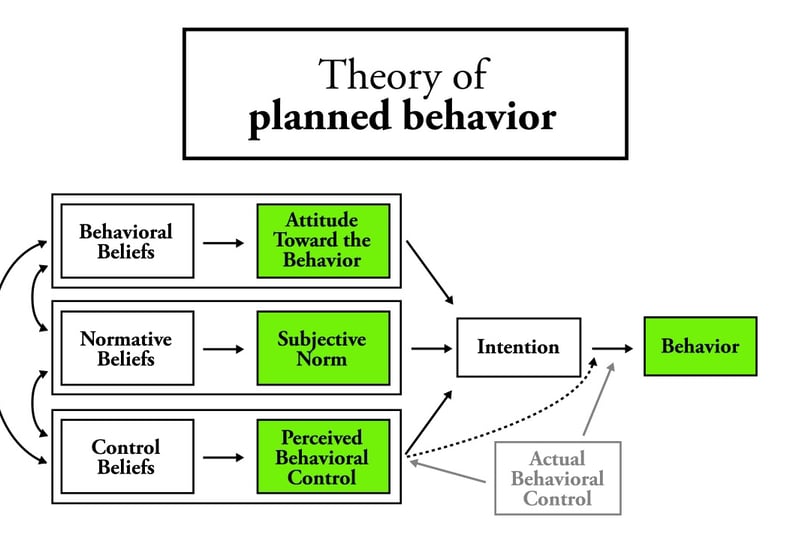

1. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The crux of any successful program lies in its ability to elicit desired behavioral and societal changes. An intervention must understand and incorporate the underlying factors that drive human behaviors and societal patterns to achieve success. That's where social and behavioral theories come into play. These theories provide a structured lens to understand, predict, and influence behaviors, ensuring effective and impactful program designs.

Let's dive into 11 widely used program design and evaluation theories, including their usage and drawbacks. These include a mix of individual and systems-level behavior and social theories:

Usage: TPB is extensively used in predicting intentions and behaviors related to health, environment, and consumer patterns. It emphasizes the individual's intention to perform a behavior, which is influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

Drawbacks: TPB often overemphasizes rational, cognitive decision-making, potentially sidelining emotional or impulsive factors that can influence behaviors.

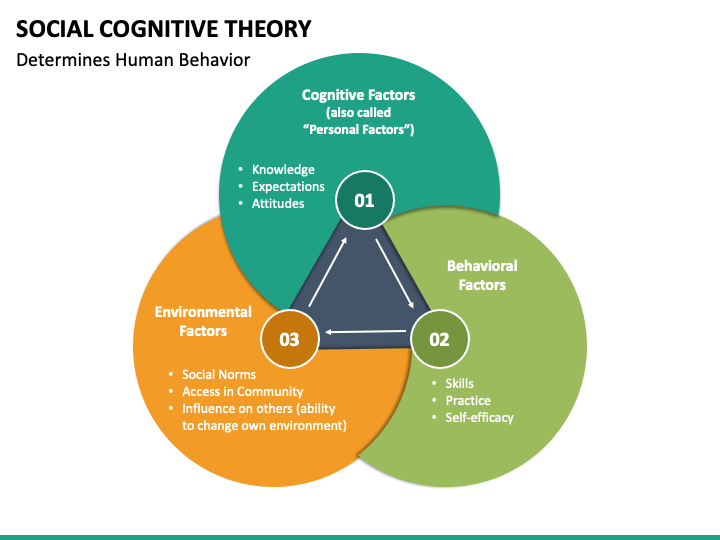

2. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

Usage: Rooted in understanding learning through observation, SCT is used in programs focusing on health behaviors and educational interventions. It underscores the dynamic interplay between personal factors, behavior, and environmental influences.

Drawbacks: It may oversimplify complex behaviors by focusing predominantly on observational learning and cognition-centric (individual-level) theories, thus neglecting other external critical influencers.

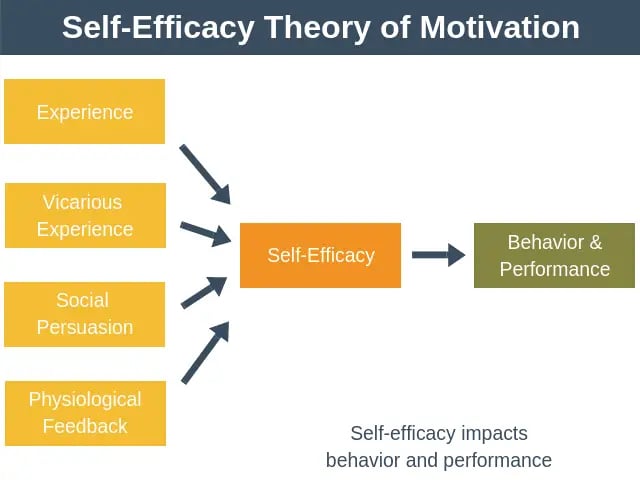

3. Self-Efficacy Theory

Usage: Predominantly found in health promotion and educational programs, this theory posits that an individual's belief in their capabilities affects their motivation and behaviors.

Drawbacks: It emphasizes individual agency, potentially downplaying the influence of external, structural factors that can affect an individual's behavior.

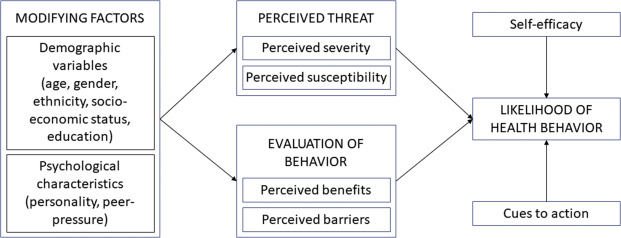

4. Health Belief Model

Usage: HBM is prevalent in public health interventions. It predicts health behaviors by gauging an individual's perceived threats, benefits, barriers, and cues to action.

Drawbacks: HBM may not sufficiently account for habitual behaviors or those performed without significant personal deliberation

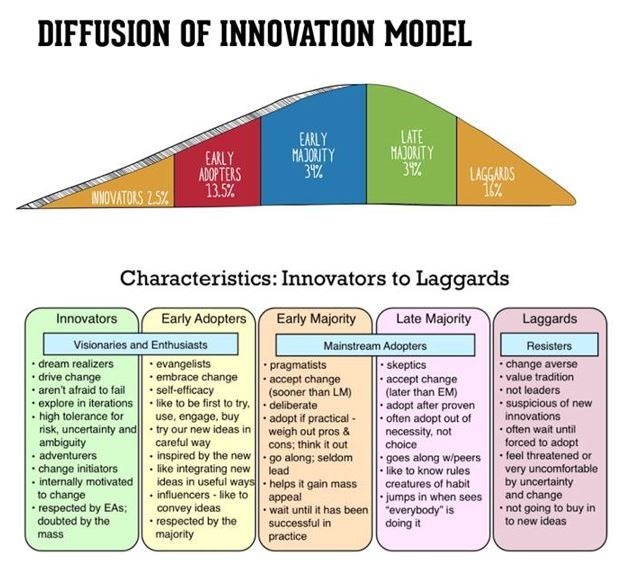

5. Diffusion of Innovations Theory

Usage: Used in programs targeting community-wide behavior change, it studies how innovations spread across members of a social system over time or what ideas "stick" and which dissipate and aren't picked up in the social arena.

Drawbacks: The theory may be less effective in predicting the uptake of innovations in highly heterogeneous communities where varying belief systems coexist and may even conflict.

6. Social Norms Theory

Usage: This theory, often applied in substance use prevention and sexual health programs, suggests that individuals perceive certain behaviors as 'normal' based on their perception of peers' actions and attitudes. In this way, pathological behaviors may become normalized.

Drawbacks: Over-reliance on this theory might oversimplify behaviors by emphasizing conformity and neglecting individual agency, external factors, and stressors.

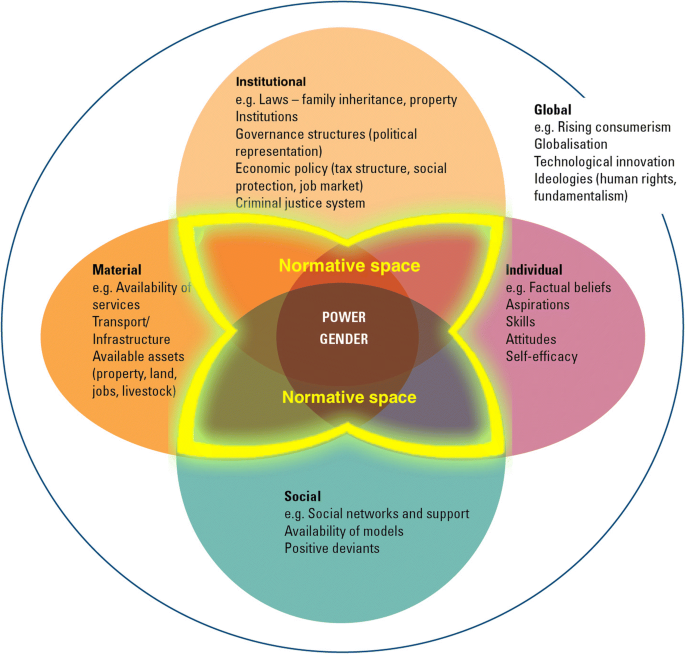

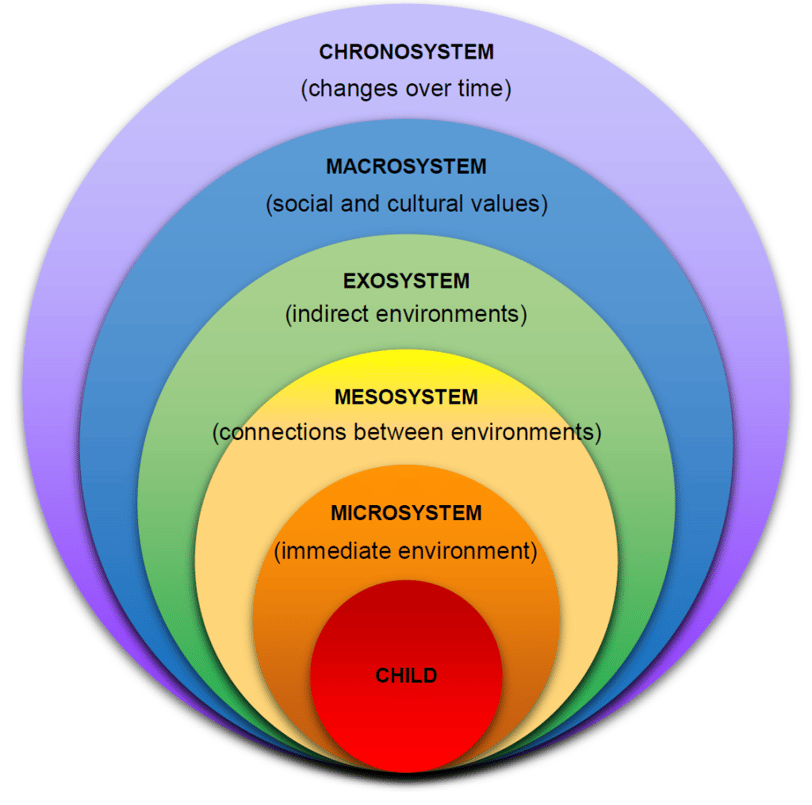

7. Ecological Systems Theory

Usage: Rooted in understanding the interplay between individuals and their surrounding systems, it's used in community-based interventions. This theory examines micro, meso, and macro environmental factors and their cumulative impact on individual behavior.

Drawbacks: Its holistic approach might sometimes spread the focus too thin, risking the oversight of critical behavioral determinants to capture too many layers of influential factors.

8. Intersectionality

Usage: Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality is widely used in programs addressing discrimination and systemic oppression. It emphasizes that individuals have multiple intersecting identities (like race, gender, and class) contributing to unique discrimination or privilege experiences. At FirstImpact, intersectionality constitutes a crucial framework and informs nearly all our work.

Drawbacks: As a nuanced and multifaceted concept, it can be challenging to operationalize intersectionality in a program design or evaluation, risking oversimplification.

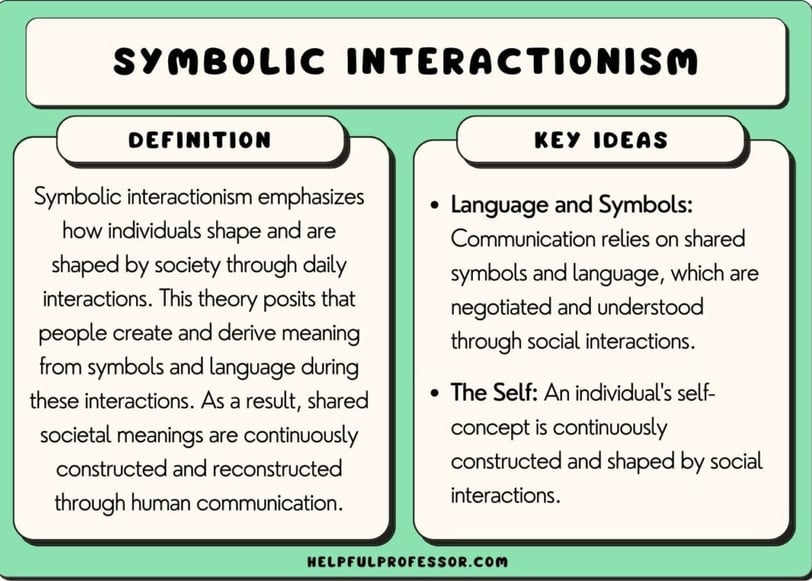

9. Symbolic Interactionism

Usage: Rooted in sociology, this theory focuses on the symbolic meaning that people develop and rely upon in the process of making sense of and navigating social interaction. It's used in programs that seek to understand and influence communal narratives and social constructs.

Drawbacks: Its micro-level focus on individual and small group interactions can sometimes overlook broader systemic or structural forces.

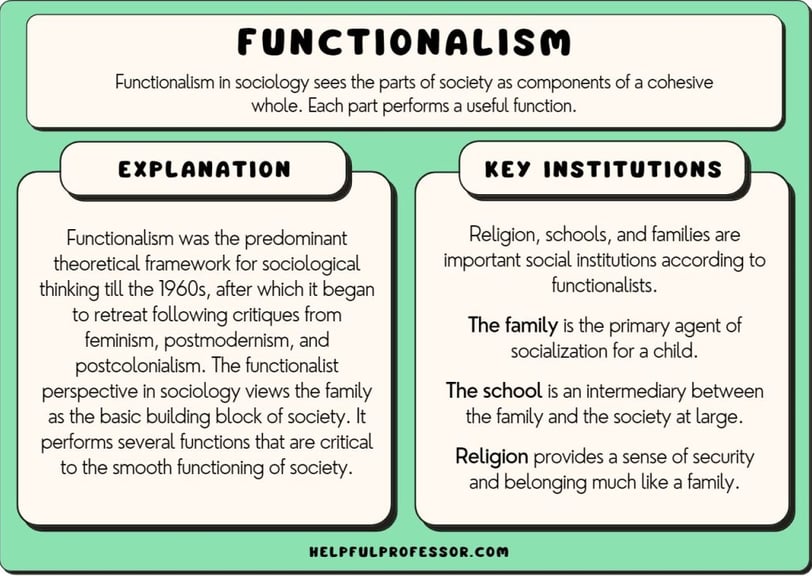

10. Structural Functionalism

Usage: This sociological framework views society as a structure with interrelated parts designed to meet the biological and social needs of individuals in that society. It can guide programs aiming to optimize social systems to serve communities better.

Drawbacks: Critics argue it can be too static, neglecting societal changes and dynamics over time, and might inadvertently support the status quo.

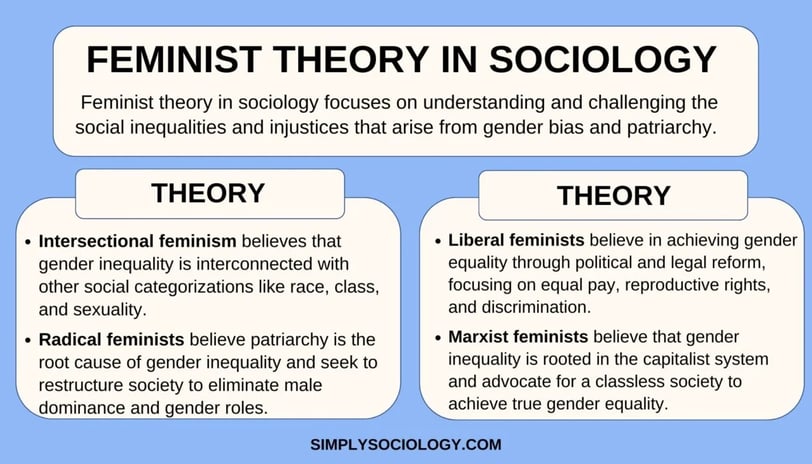

11. Feminist Theory

Usage: Feminist theory examines the roles, experiences, and challenges of women and LGBTQ+ members in society. It's foundational in programs addressing gender inequities, women's rights, and dismantling patriarchal structures rampant in modern society.

Drawbacks: There's a risk of essentializing women's experiences or those of gender minorities, overlooking the diverse experiences of women and minorities across different cultures, races, and socio-economic statuses.

Why the Right Theory Matters

Leveraging a mix of these theories helps fully capture the intricate web of social, cultural, and systemic factors that influence individual and group-level behaviors. They draw attention to the power dynamics, systemic barriers, and social constructs that often get overshadowed by individual-focused behavioral theories. The theory you choose, however, depends on the program and its objectives.

Choosing the proper theoretical framework is more than an academic exercise—it's a strategic imperative. It shapes the program's design, its implementation strategy, and the metrics constructed to measure its success.

An adequate theory illuminates the underlying mechanics of behavior change, offering tangible touchpoints to design short- and long-term interventions. A well-operationalized theoretical framework provides a roadmap to navigate complex behavioral patterns, ensuring the program remains relevant, resonant, and impactful.

Conversely, a misfit theory can misguide interventions, leading to ineffectiveness, inefficiencies, or disagreements in what the program achieved or what the evaluation data collected means.

As we push the envelope in driving societal change through various programs, anchoring them in robust theoretical frameworks is critical and pragmatically beneficial. The symbiosis between theory and practice ensures our efforts translate into tangible, transformative results, underscoring the lasting legacy of well-designed interventions.